Dennis Carroll

Chief Scientist

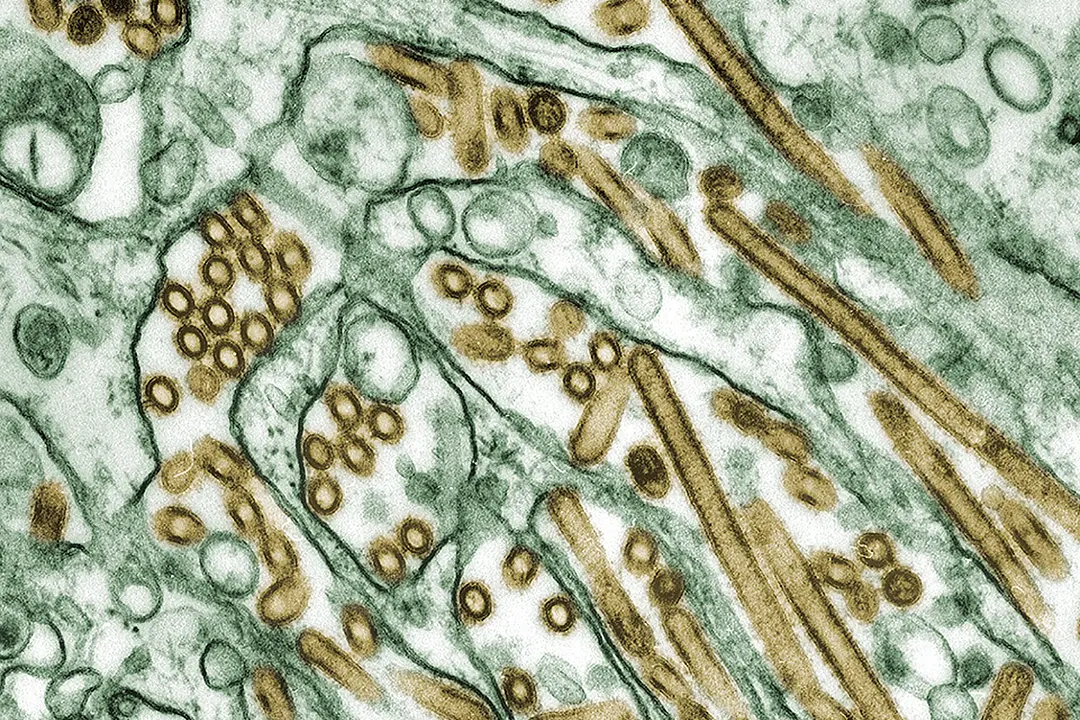

Avian Influenza is back, and the world largely is yawning, but we should be alarmed. This highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus was first reported in Hong Kong in 1997. As an avian virus, it is highly transmittable among poultry and lethal: it kills 100% of the poultry infected. As an immediate threat to humans, however, it is very limited as it lacks the genetic coding that would enable efficient human infections, but on the occasions that humans have been infected it has proven to be extraordinarily lethal, killing more than 50% of those infected.

By comparison, the SARS-COV2 virus (COVID-19) killed less than 0.1% of those it infected. As an influenza virus, H5N1 belongs to the family of viruses that have caused some of the most devastating pandemics in history, most notoriously being the 1918 pandemic that killed an estimated 50-100 million people worldwide.

The scientific community understands that only a handful of mutations are required in the H5N1 virus to transform it into a more infectious agent, like the seasonal flu, which moves easily from person to person. Allowing the virus to spread uncontrolled through poultry, with the occasional human infections, was a recipe for equally uncontrolled mutations elevating the risk of the H5N1 becoming a truly pandemic virus unparalleled in human history.

Swift Coordination Made the Difference in 2005

In 2005, the H5N1 virus began spreading rapidly from Asia, across the Middle East, and into Europe and Africa, killing hundreds of millions of poultry and dramatically raising worldwide concerns. The global response was equally dramatic and swift. A global coalition, with significant leadership from the U.S., quickly deployed resources and personnel to bring the spread of the virus under control. USAID and the program that I ran at the time, the Emerging Threats Program, played a significant role in building systems and capacities in more than 50 countries to bring this threat under control.

By 2007, the number of countries infected with this virus had dropped from a high of more than 65 countries to fewer than seven, mostly in Asia. Widespread use of enhanced biosecurity measures on farms and the availability of a highly effective H5N1 poultry vaccine dramatically reduced the global threat from this virus. The Emerging Threats program continued to support efforts to control the virus in the few countries where it continued to circulate. The program also monitored for any changes in its epidemiology or genetic profile that could signal a renewed threat. The world breathed a collective sigh of relief.

With All Eyes on COVID-19, H5N1 Spreads

Fast forward to 2020. With much attention focused on SARS COV2 (the COVID-19 virus), the H5N1 virus once again began spreading uncontrollably. In 2022 a strain of H5N1 caused an outbreak in farmed mink in Spain, and in 2023 farms in Finland reported infections in mink, foxes, raccoon dogs, and their crossbreeds. On both occasions the outbreaks signaled that the virus was not only spreading but had evolved to infect mammal populations. In the summer of 2022 outbreaks among harbor and gray seals in eastern Quebec and on the coast of Maine signaled the virus for the first time has spread into North America. Brazil reported their first H5N1 outbreaks in 2023, indicating the virus was now widely distributed on virtually every continent.

The sense of urgency and global solidarity that had characterized the response in 2005 was absent. On March 25 of this year the H5N1 saga took on an even more alarming twist – a multistate outbreak of H5N1 bird flu was reported in dairy cows and on April 1 the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first H5N1 human infection in a person with exposure to dairy cows. Since then, H5N1 infections of dairy cows have been confirmed at more than 80 farms in nine states (as of June 5) with four confirmed human cases.

We Don’t Know What We Don’t Know about H5N1

This, unfortunately, is likely the tip of the iceberg. The domestic surveillance for H5N1 being mounted by CDC and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) is fragmented and largely based on voluntary reporting. There has been only scant monitoring for genetic changes in the virus that could signal greater risk to humans. And the sharing of viral sequences collected from cows is moving at an alarmingly slow pace. We don’t know how widely distributed this virus is among U.S. dairy herds and dairy workers.

Even more alarmingly, there appears to be no significant monitoring of farm pigs, either domestically or internationally, for possible infections by H5N1. This is of particular concern because pigs, unlike cows, are also host to the very influenzas that infect us every flu season. Were the H5N1 virus to infect a pig that is co-infected with a seasonal flu (i.e. H1N1 or H3N2) that has the genetic profile that enable high transmissibility among humans, there is a very real possibility that through the exchange of genetic material between the different viruses – a common phenomenon known as “gene swapping” – the H5N1 virus could acquire the very profile that would make it a highly infectious threat to humans. Were this to happen the COVID-19 pandemic would look like a garden party.

If there’s one lesson we should have learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s the importance of timely and comprehensive surveillance and the essential requirement for global coordination. The global spread of the H5N1 virus and its steady march to diversify its host species signals the real possibility that sooner than later the virus will acquire the necessary mutation to wreak havoc among human populations. As has been repeated many times, a threat anywhere is a threat everywhere. In 2005, it was the combination of surveillance and coordination that enabled the successful control of the virus. It was the absence of these two features which led to the devastation of COVID-19.

Work Together or Risk the Consequences

The fragmentation of global politics and the lack of urgency are only elevating the risks of H5N1 emerging as the next and far more deadly pandemic virus. The U.S. urgently needs to overhaul its domestic monitoring of the virus by CDC and USDA to ensure a timely and transparent monitoring across all livestock and high-risk human populations, as well as the real time sharing of genetic data

And, as the U.S. did in 2005, it needs to galvanize a global effort to bring this threat under control, with leadership from USAID. We’ve seen the success when coordinated action is taken and the consequences when it is not. The world must stop yawning, it’s time to wake up and act. The next pandemic may not be as forgiving as the last.